PRESIDENT Online

Yasufumi Murayama

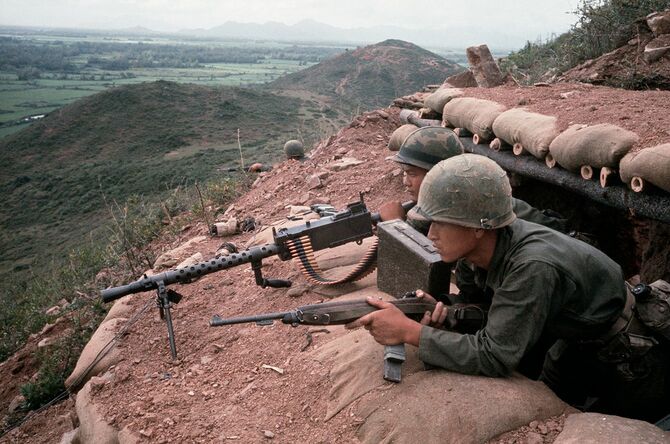

From 1964 to 1973, South Korea dispatched a total of more than 300,000 soldiers to support the United States in the Vietnam War. It is known that a large number of civilians were massacred during the war. Photojournalist Yasufumi Murayama said, “I visited a local newspaper and was able to hear the modus operandi of the massacre. The actions of the South Korean military were nothing short of insane” – he said.

To Vietnam to cover the incidents allegedly committed by the South Korean military

In June of the same year, four months after my February 2014 trip, I landed for the first time in Thuy Hoa City, the capital of Phu Yen Province.

They shot 30 villagers and blew them up with grenades to cover up the incident.

I shook hands with Editor-in-Chief Binh and told him the reason for my visit on the sofa in the lobby. He then stood up and said, “Please wait a moment,” and brought two books from the editorial director’s office. The two books were a compilation of local histories compiled by the editor-in-chief, Mr. Binh.

Although not mentioned in these two books,” Binh said quietly, “during interviews in other prefectures where we are preparing the book, we have heard many unbelievable accounts, such as ‘gang-raping women, cutting off their breasts with a knife, and then killing them by stirring their genitals with a bayonet,’ and ‘killing infants by throwing them like a ring toss onto a bayonet held by a soldier. Binh spoke quietly. The actions taken by the Korean soldiers in the village where the incident is alleged to have taken place are quite insane.

In the village of Phu My, Hua Dong, they shot all 30 villagers, threw them into three wells, and threw grenades into the wells to cover up the incident as if nothing had happened.

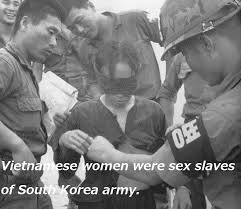

Ten Korean soldiers gang raped a young woman, who was later shot and killed.

In the village of Chuong, Hoa My, 16 people were killed. Six members of a family were killed, including two elderly, a pregnant woman, and a disabled woman.

In My Thung and Quang Phu villages in Hoa My Company, soldiers captured seven women, raped them one by one, and then bayoneted two of them to death. The remaining five women were taken into the forest, stripped naked, tied up tightly, and gang-raped by top Korean soldiers. They then stabbed the five women and one infant to death. They killed the infants by throwing them like a ring toss onto the soldiers’ bayonets.

The attack by the South Korean troops, who broke into the village from the north, quickly claimed the lives of 37 residents on the spot. Most of them were old men, women, and children, I was told by Binh, editor-in-chief of the Phu Yen Newspaper, whom I had just visited.

According to Pham Tua (75 years old = as of March 2017), a former Vietcong soldier who lives in Da Ngu village, where Vung Tau settlement is located, the Korean army was planning to clear the forest in the area of Da Ngu village to build a base. Initially, the ROK military tried to separate the civilians from the Viet Cong and protect the civilians, but the ROK soldiers were unable to distinguish between the two and went on to kill the villagers, he said.

The stone monument in Vung Tau village was erected in 1975, soon after the war ended, so it was probably carved as a “hate monument” rather than a “memorial. As I was taking pictures of the “hate monument,” a middle-aged man passing by on a motorcycle asked me, “What are you doing? He asked me, “What are you doing?

When I explained to him why I was here, he kindly showed me around and said, “There is a woman named Nguyen Thi Manh (68 years old as of June 2014) who knows about the incident living at the end of this alley. I entered the square where the “Monument of Hatred” is located and walked along a concrete paved pathway for a short distance. A man called out to me in front of the house from which the chicken had emerged, “Mr. Mann, you have a visitor. The man’s caring nature made me giggle and wonder if I knew all the people in the countryside.

He gunned down the residents begging for their lives and finally threw a grenade into the air.

Mr. Mann came out of the house, wiping his hands on a towel, probably washing dishes. When Mr. Mann saw me, his relaxed face suddenly stiffened and he whispered, “Are you Korean? He whispered, “Are you Korean? No, I’m Japanese. I am Japanese. When I answered, his expression softened a little.

Since I began reporting in central Vietnam, I have often been mistaken for a Korean in the villages where the Lai Dai Han people live and where the Korean military is believed to have killed civilians. I have been blatantly ignored, especially by people of the generation who knew about the Vietnam War, and I have sometimes felt that I was clearly being shunned.

About a month ago, I saw several Koreans paying their respects at a stone monument. I still get scared when I see Koreans. Mann invited Dao and me into his home. He then slowly recounted the events of the time of the incident.

……At about the same time the sun was rising, we heard the sound of helicopters, and Korean soldiers broke into the village from the north. The villagers gathered their families and went outside because if they hid in their houses they would be mistaken for Vietcong. Almost all the men fled the scene because they were afraid they would be killed.

Then all the old men, women, and children were gathered in the square, not knowing what to do with them. I thought they would never touch the women and children, but the Korean soldiers took aim at them with their guns. Everyone was surprised and begged for their lives. However, the Korean soldiers shot and killed them one after another as they begged for their lives, and finally threw a hand grenade into the air. I was watching the incident from a tree a short distance away, and my uncle took me by the hand and we escaped together to the back of the mountain, where we were saved.

Mr. Mann’s face was saddened as he said this.

The “hate monument” is turning into a “memorial.”

Mr. Manh, whom I met this past year (June 2014), was no exception. Whenever I was in the vicinity of Phu Yen Province for interviews, I would always visit Mr. Manh’s home. And each time I visited Manh’s house, I would see the “change” in the stone monument in Vung Tau village nearby.

The stone monument, erected shortly after the war, was painted white in color in August 2016, with the words “hate monument” written at the top of the monument. Furthermore, in October 2017, the monument changed its shape and was rewritten to read “Cenotaph” and inscribed with the names of 80 victims (7). (7) When I visited Vung Tau village in February 2018 after the monument was renamed the “Cenotaph,” I recalled the words of Binh, editor-in-chief of Phu Yen Newspaper, who once told me, “In 1992, the Vietnam-Korea diplomatic relations were established.

After the restoration of diplomatic relations between Vietnam and Korea in 1992, relations between the two countries have gradually improved.” Now, in order to forget the past, the Vietnamese government is trying to change the ‘hate monument’ in the village where the Korean military allegedly killed civilians into a ‘cenotaph’ for the victims.

The word “hatred” may have disappeared from the stone monument, but it will never disappear from the hearts of the victims who experienced the incident.